Learn about brain health and nootropics to boost brain function

Neuroimaging study finds people who exercise more display an elevated brain response to reward

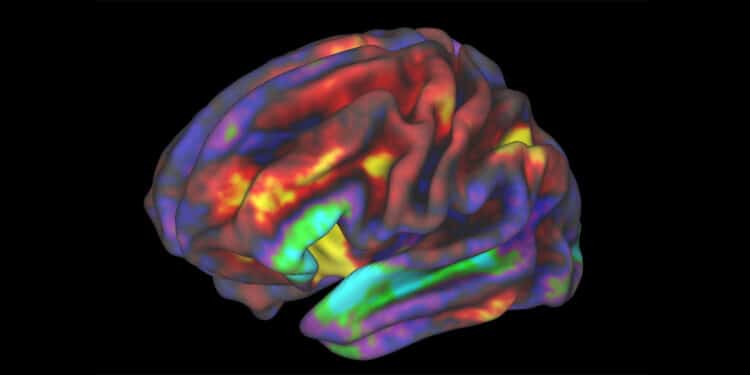

(Photo credit: Richard Watts/NIH Image Gallery) New research published in the journal Biological Psychology revealed that people who exercise more show increased brain activity when receiving an unexpected reward, specifically in the right medial orbitofrontal cortex. These findings may suggest that regular exercise alters the reward-circuit function, potentially reinforcing exercise behavior.

The physical and mental health benefits of exercise are widely known, yet finding the motivation to exercise can be a challenge. The authors of the study said that a look inside the brain may shed light on how people can be encouraged to maintain healthy exercise habits. More specifically, the dopamine reward system may play a role in motivating people to exercise, and the study authors proposed that regular exercise might alter the brain reward response.

“My background is in eating disorders research and those individuals frequently engage in very high amount of exercise. Before we explore the effects of exercise in that population, I wanted to study the relationship between exercise and brain reward processing, specifically dopamine-related reward processing,” said study author Guido K.W. Frank of the University of California, San Diego.

The researchers examined brain activity during a reward prediction error (RPE) task. An RPE is when a person receives an outcome of an event that is different than expected, causing dopamine neurons to send out a signal. This unexpected outcome could be positive, like receiving an expected reward, or negative, like having a reward unexpectedly taken away. The RPE is thought to reflect motivational salience — a cognitive process that drives a person’s behavior toward a positive outcome. The researchers speculated that people who exercise more often might show a stronger salience response in the dopamine system.

“The type of reward system response that we focus on responds to unexpected stimulus receipt – one could say excitement over receiving a reward unexpectedly, or unexpected stimulus omission, or disappointment over not receiving a reward that was expected,” Frank told PsyPost. “The stimuli we use are taste stimuli sucrose or water.”

A group of 111 healthy women participated in a task that evoked the dopamine-related RPE response. The task involved a classic sucrose taste-conditioning paradigm where participants learned to expect or not expect a sucrose reward. Throughout the task, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was used to measure participants’ brain activity. Additionally, the women reported how much aerobic exercise they engage in on a weekly basis.

The researchers then analyzed the fMRI data, focusing on brain responses when participants either unexpectedly received a sucrose reward, unexpectedly did not receive it, or expectedly received it. For all three conditions, increased exercise was associated with a stronger response in the right medial orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). But after correcting for multiple comparisons, this heightened activity was only significant during the unexpected receipt condition.

“Higher amount of cardio/aerobic exercise was associated with higher brain response (orbitofrontal cortex, an area between the eyes that is important for valuation of rewards) when participants received the sugar stimulus unexpectedly, but did not affect the response to unexpected stimulus omission or disappointment,” Frank explained. “We believe that higher amount of exercise might change your brain that receiving a reward unexpectedly is more enjoyable.”

Notably, the right medial OFC is implicated in goal-directed decision-making and the calculation of reward value. The findings may suggest that exercise strengthens this circuitry, driving higher brain activity in the OFC. Alternatively, it could be that higher activity in the OFC reinforces engagement in exercise.

“It is therefore possible that individuals who engage in more aerobic activity may be intrinsically more responsive to salient stimuli and especially stimulus receipt,” the researchers wrote, “or alternatively, engagement in aerobic exercise has modulated brain activity and dopamine signaling, which may then reflexively reinforce and functionally maintain the exercise behavior.” The authors note that both of these explanations could be true.

Overall, the results suggest a link between aerobic exercise and the brain’s response to unexpected reward. “It is possible that exercise may in particular enhance the ability to value or enjoy stimuli or experiences, which could be important for intervening on psychiatric disorders,” the authors said, adding that an “altered brain salience response is characteristic of many psychiatric Illnesses.” If exercise is found to improve motivational salience, this could reveal potential treatment options for affected individuals.

Among limitations, the study was cross-sectional, and future longitudinal studies will be necessary to draw stronger conclusions from the data. Additionally, participants self-reported their exercise levels, and it is unclear whether the findings reflect the effects of overall activity level or true aerobic exercise.

“We cannot be certain what neurotransmitters are exactly involved and a larger study sample might have indicated that higher cardio exercise is also protective of disappointment,” Frank said. “It is possible that cardio exercise helps to be happier in being able to enjoy things more and be less disappointed when something does not work out the way you thought.”

“It is important that this was a study in healthy controls and their exercise amount was within normal limits,” he added. “Excessive exercise can get in the way of healthy living and will not have a positive effect on your wellbeing because you may lose much weight and/or develop an eating disorder.”

The study, “ Associations between aerobic exercise and dopamine-related reward-processing: Informing a model of human exercise engagement ”, was authored by Sasha Gorrell, Megan E. Shott, and Guido K.W. Frank.