Learn about brain health and nootropics to boost brain function

Is Depression a Sign of Low Brain Energy?

New science offers a practical model for understanding and treating depression.

New research suggests that depression could be caused by reductions in energy metabolism in the brain.

The human brain is incredibly energy intensive; even small deficits in energy production can have major consequences.

Improving our lifestyle habits is a powerful tool for preventing or reversing depression by up-regulating our brain’s energy potential.

One of the most promising new theories for understanding depression is as the result of impaired brain energy metabolism (1). The human brain is an incredibly energy-intensive organ. Weighing in at a mere 3 pounds or so—just 1-3 percent of total body weight for most people—the brain accounts for a remarkable 25 percent of the body’s total energy consumption when we are at rest. Realizing the massive energy demands of the brain, it becomes clear that even small deficits in brain energy metabolism could have potentially dire implications for how we feel and function.

Brain energy metabolism is essential to life and depends on the ability of brain cells (neurons) to convert fuel sources (e.g., food and calorie-containing beverages) into a specific form of cellular energy called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). What many people don’t realize about brain metabolism is that the ATP process can be impaired even when there is plenty of fuel available. Known as metabolic dysfunction, this results from neuronal changes that compromise their ability to create ATP.

One of the common sources of metabolic dysfunction occurs when brain mitochondria—the energy-producing powerhouses inside neurons—can no longer create enough ATP to keep up with energy demands. When mitochondrial dysfunction takes place, it is the equivalent of a plant losing the capacity to convert sunshine into energy or a stove incapable of burning wood to produce heat. In the case of neurons, cellular processes vital to health, thinking, and feeling may cease entirely or continue only in a diminished capacity.

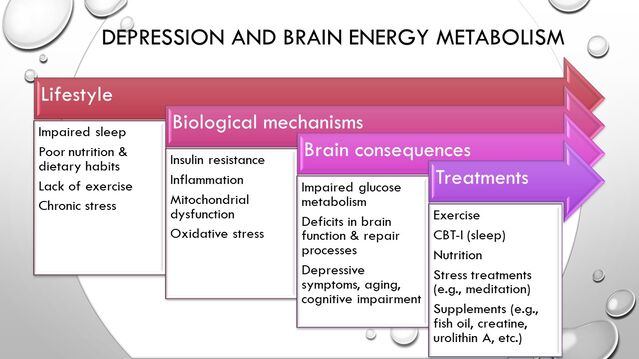

Given the latter, it is perhaps not surprising that neuroimaging, genomic, and metabolic research has identified mitochondrial dysfunction in the brain as a potential cause of depression, as well as being a possible common cord connecting depression to overlapping conditions, such as cognitive impairment, hypothyroidism, and even aging (2). This research also suggests that the people most vulnerable to depression caused by impaired brain metabolism are those with other metabolic health conditions (e.g., diabetes/pre-diabetes, insulin resistance, fatty liver, obesity, PCOS, hypertension) and lifestyle factors putting them at risk for metabolic diseases. How health habits become brain function. Source: Thomas Rutledge

The image above illustrates a general causal model for how depression and brain energy metabolism deficits may begin years or even decades earlier from unhealthy lifestyle patterns. These factors, over time, trigger adverse physiological processes that can lead to metabolic diseases in the body and metabolic dysfunction in the brain. As these processes advance, neuronal function gradually becomes compromised to such a degree that it may eventually manifest in subjective symptoms, such as lack of energy or motivation , memory and concentration difficulties, and other depressive symptoms that are likely to vary from person to person.

Because this chain of events begins in most cases from modifiable health behaviors, it follows that behavioral interventions should theoretically be amongst the best methods to reverse these processes, improve brain metabolism, and treat depression. Recent clinical trials research supports this theory strongly. In fact, the emergence of brain metabolic dysfunction as a theory for depression offers an appealing model for understanding how behavioral treatments as seemingly different as exercise, CBT for insomnia (CBT-i), meditation , and dietary changes such as intermittent fasting have each been shown to improve depression for many individuals. All of these—through a combination of biological mechanisms—improve brain metabolism and mitochondrial function.

Read more at www.psychologytoday.com