Learn about brain health and nootropics to boost brain function

Motoring on: UCC gut-health expert looks forward to new challenges

Motoring on: UCC gut-health expert looks forward to new challenges

As he prepares to leave UCC, Prof Ted Dinan recalls the early-morning moment he coined the word psychobiotics, a term describing how bacteria in the stomach can influence our mood, writes Helen O’Callaghan

TED Dinan was due to give an 8am lecture at a symposium in Dublin. It was a Sunday in 2012 and he wished he could be anywhere else. But in those moments of musing on what else he could have been doing, a word flashed into his mind. The word was ‘psychobiotic’ — Dinan had just coined a term to describe mood-improving microbes or bacteria.

Professor of psychiatry and a principal investigator in the APC Microbiome Institute at UCC, Dinan will retire from academic medicine this autumn. He was previously chair of Clinical Neurosciences and professor of Psychological Medicine at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London. His 16-year stint at UCC has been his longest job. “I’ve never stayed anywhere very long. It’s important to move out of your comfort zone intermittently. I’ve stayed here because it’s been very productive and I enjoy the people I work with.”

Chief among these is John Cryan, professor and chair of the Department of Anatomy and Neurosciences at UCC and also a principal investigator at APC Microbiome, a leading-edge institute researching the role of microbiome in health and disease.

“The primary focus of research in our labs — the core of what we do — is how microbes in the gut influence the brain and influence behaviour,” says Dinan.

“Ten years ago we weren’t aware that gut microbiota [community of microbes living in our gut] is part of our stress system. Now we know if our gut microbiota is altered, our capacity to deal with stress is altered too.”

In The Psychobiotic Revolution: Mood, Food and the New Science of the Gut-Brain Connection,

Cryan and Dinan teamed up with journalist Scott C Anderson to tell the intriguing story of how our gut controls our brain. A better-balanced gut can improve anyone’s mood, they say — it can even improve your thinking and boost your memory. Cryan and Dinan say their research shows the gut-brain connection to be like Downton Abbey — two communities living together in the one house, needing each other to survive, but largely ignoring each other.

“It’s only when things go wrong downstairs that the real drama occurs upstairs.”

The authors point to an epidemic of depression today without an obvious external cause – and to an epidemic of gut problems. “These two are strongly associated. Research continues to reveal connections between gut health and other diseases both mental and physical. Depression accompanies many of these diseases, including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, arthritis, MS and autism.”

Citing IBS as a very common gastrointestinal problem affecting up to 10% of the population, Dinan says there’s evidence the microbiota of IBS patients is altered. “At least half of patients with IBS have depression and anxiety. Here’s a gastrointestinal condition where microbiota is altered and there’s high co-morbidity of depression/anxiety.”

At his office in the BioSciences Institute, UCC, Dinan speaks of three of the most important routes of communication between gut microbes and the brain: Microbes can signal through the vagus nerve, a long meandering conduit between brain and internal organs, including the gut. As well as that, certain microbes produce short-chain fatty acids, for example, butyrate, which can have a profound effect on the way many organs in the body function, including the brain. And then there’s tryptophan, an amino acid and building block for serotonin.

“Serotonin’s involved in regulating mood, sleep, appetite and a wide variety of processes. It used to be thought all Tryptophan came from our diet — we’ve shown that certain bacteria are capable of producing it,” says Dinan. This is important because the human brain has very limited storage capacity for Tryptophan.

“We need a constant supply in our blood system to replenish supply in our brain. If we don’t have enough serotonin in the brain, we won’t function normally.”

Up to 20 years ago, bacteria were largely viewed as dangerous. “We now know bacteria have very important roles in normal physiology,” says Dinan, adding that this goes back to our beginnings — and to birth.

“Babies born through the vagina have very different microbiota for the first three years to those born by C-section. When a baby’s brought out by C-section, the first bacteria it’s exposed to is on the doctor’s skin, mum’s skin. When baby’s born through the birth canal, the first bacteria it’s exposed to are lactobacilli in the mum’s vagina, which are very good bacteria.”

In fact — as is pointed out in The Psychobiotic Revolution — lactobacilli produce GABA, a key neurotransmitter that can have a tranquilising effect, dialling down anxiety.

What red flags indicate our gut health isn’t working optimally? “With an unhealthy microbiota, one’s capacity to deal with stress isn’t as good as it should be,” says Dinan. And how can we improve gut health? The two important influences are diverse diet with plenty fruit and vegetables, along with vigorous aerobic exercise. “I advocate running, swimming or cycling – it must be vigorous.”

He emphasises that healthy ageing is about maintaining diversity in the microbiota. “Lack of diversity tends to lead to frailty in the elderly. Poor diet is undoubtedly the main contributory factor, the really significant one, to an unhealthy microbiota.”

The general consensus, he says, is that fermented foods — yogurt, sauerkraut — have health benefits. And to have a good microbiota, we should be taking in a lot of prebiotics – fibre that acts as food for the psychobiotics.

“The most widely studied prebiotic is inulin – found in Jerusalem artichoke, celery, onions, garlic, bananas, potatoes and in wheat products too. Inulin promotes growth of good bacteria.”

It goes without saying, says Dinan, that if somebody takes multiple courses of antibiotics, it wipes out the microbiota and has “a very negative effect”.

When it comes to probiotics and mental health, Dinan says most of those he and Cryan have tested have no impact. However, they have identified one or two bacteria that seem to have an anti-anxiety effect. “The most recent is Bif Longum. Certainly in our labs, we’ve shown it has anti-anxiety effects in humans. We think they’re probably significant. We’ve seen it improve sleep. And it decreases output of cortisol – the main stress hormone. Most probiotics are not psychobiotics, but Bif Longum is a probiotic that’s a psychobiotic too.”

He says it’s too early to tell if psychobiotics are as effective as anti-depressants — we don’t have that data. (“In fact, we’re in the very early stages of learning about the gut. I’m not sure in 20 years we’ll have unravelled all the complexities.”) But Dinan hopes we will have a psychobiotic for dealing with milder depression/anxiety. “Right now, if you go to your GP with mild depression, you might be offered an anti-depressant, counselling or, if lucky, be referred for CBT. For milder forms of depression, a natural alternative like a psychobiotic would be of value.”

One in 10 people suffers from depression at any one time, according to support organisation Aware. Dinan runs a clinic treating refractory depression at CUH. “I use different combinations of medicines to what others might use. I use CBT. I combine these traditional treatments with advice about diet and aerobic exercise. I’ve seen people who were failing to respond to traditional treatments — who, after changing their diet over just a few weeks — come back reporting big improvements.”

He cites a good diet as Mediterranean-type, with wide variety of fruit, veg, nuts and fish.

Recalling one recent patient, a mother of two relatively young children, he says: “She’d been depressed at least six months. She’d been treated with anti-depressants and had seen a counsellor. She was happily married and had no major financial problems or issues that could be identified as causing the depression. She was very busy and her diet was less than optimal. I put her on a fairly modified Mediterranean diet and she jogged for 20 minutes a day, five days a week. After three to four weeks, there was really dramatic improvement in her mood. I’ve no doubt exercise and diet played a very important part in her recovery.”

In fact, says Dinan, he’d love to educate psychologists/psychiatrists to enquire more about patients’ dietary habits. “Patients are rarely asked by these professionals about their diet.”

In their lab, Dinan and Cryan showed they could transfer ‘the blues’ with gut microbes — they transplanted faecal matter from human patients with major depression into rats and saw the rats became depressed too. Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been resurrected in recent years, says Dinan, explaining that 2,000 years ago the ancient Chinese gave ‘yellow soup’ to treat illnesses — this was essentially faeces.

“Today, people are experimenting with using FMT for all sorts of things. I get emails asking whether it can be used for MS or depression. There’s no evidence to suggest these conditions would respond to FMT.”

However, in Cork, FMT has been used to treat patients with clostridium difficile. A very difficult condition to treat in the elderly, it causes chronic diarrhoea. “FMT has had success rate of about 90%,” confirms Dinan, adding the donor’s mental health must be taken into account. “If the donor’s suffering from depression/anxiety, there’s a danger it could be transmitted to the recipient.”

Married to CUH consultant Lucinda Scott, Dinan himself is “reasonably healthy”. He’s on no meds but confesses to a “terrible” sweet tooth. “It’s absolutely shocking. I could eat apple pie every day. But I eat plenty of fruit, vegetables, fish, nuts. I run most days. I have since I was a kid— running comes natural to me. I’ve run dozens of marathons.”

Raised in the Cork City suburb of Douglas, Dinan played some rugby while at secondary school in Christians.

“I love rugby but I was no great shakes at it. I love watching Munster Rugby. I love soccer. I follow League of Ireland — I’ve been going out to Turners Cross since I was three.”

It was at Christians he decided he’d be a doctor. “I was in first year and Mr McCarthy, our science teacher was talking about the human body. There and then I decided I’d be a doctor — there were no medics or academics in my family. When I look back, it was always biology that fascinated me and that’s why I became an academic. Academic medicine suits me. I wouldn’t recommend it to my kids — you’re as good as your last paper — but I like it.”

A father of three, Dinan’s daughter, Vicky’s a primary schoolteacher in California. His son is studying law at UCC and his youngest is doing her Leaving Cert this year and wants to do medicine. Dinan — who also has a double psychology from UCC’s Department of Applied Psychology — will “bow out” of the day job this autumn.

“I don’t want to take another academic medical post, though I’ve been approached by one or two universities, which surprised me — I thought once you hit 60... I’ve a number of business activities I plan to engage in. I’ll take a few weeks before deciding.”

A lover of coffee shops and bookshops, he reads a novel a week and is currently reading Austrian writer Stefan Zweig’s Impatience of the Heart.

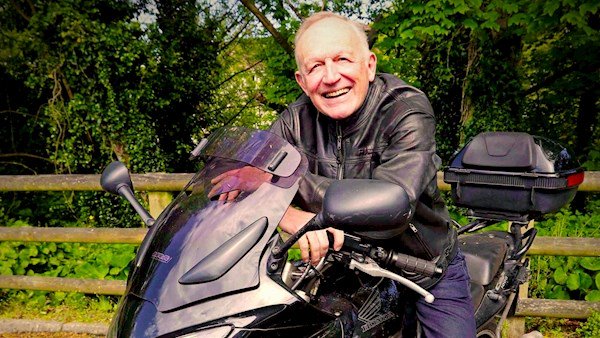

He also loves to travel. “I’d like to go off back-packing for a few months. I wouldn’t mind taking my motorbike down the south of Spain.”

An apt image for a man who has done much to show that – while our gut microbes can influence our mood and behaviour – we can put ourselves back in the driver’s seat by making some definite changes to our diet and exercise regimen.

News Daily Headlines

Receive our lunchtime briefing straight to your inbox

Click here to view full article