Learn about brain health and nootropics to boost brain function

Siegfried and Roy: What Happened the Night of the Tiger Attack?

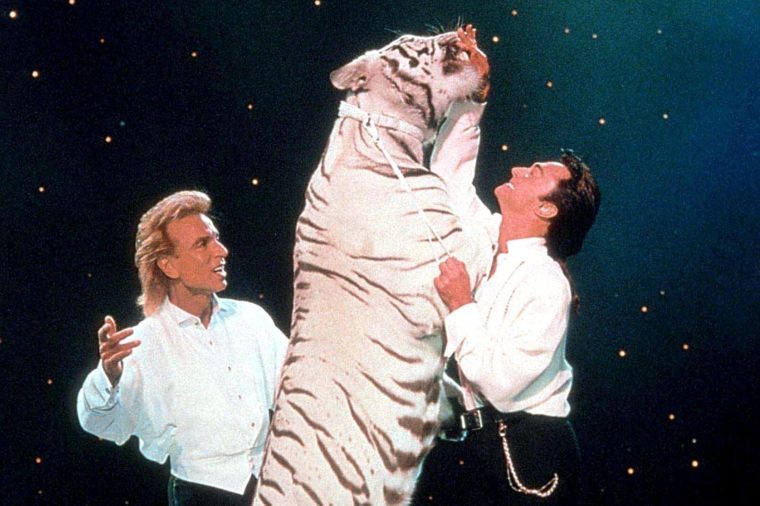

At his lavish 59th birthday party in the Mirage Hotel theater that bears the duo’s name, Roy Horn, the dark-haired half of the team, ushered in the early hours of the morning with 500 friends and fellow entertainers. He had spent the evening table-hopping and dancing, and at midnight raised a glass to his partner, Siegfried Fischbacher, in celebration of their 44 years together.

“He was in great spirits,” remembers impersonator Frank Merino, an invited guest. “All of his friends were kidding around with him, and he was making jokes and being very playful.” One of the jibes was about his age and eventual retirement.

“I’ll retire only when I can’t do it anymore,” Roy shot back in his heavy German accent, alluding to the physical strength necessary to swing on ropes 30 feet above the audience and handle the 600-pound tigers that were the centerpiece of the act. To a man so fit and lithe, that day seemed a long way off. “It is incredibly dangerous, and we took Roy, this superman, for granted all of these years,” says fellow Vegas magician Lance Burton.

But less than 24 hours later, Roy lay near death in the trauma unit of University Medical Center. Even in a town famous for risky wagers, few were betting he would survive the night. In 30,000 perfectly timed shows with elephants, lions, tigers, cheetahs, and sharp-beaked macaws, Siegfried & Roy had never had a serious mishap. Their act, seen by some 400,000 people each year, was a pastiche of Vegas razzle-dazzle: daredevil theatrics, illusions and, of course, animals.

The lions and tigers were Roy’s domain, and his ability to communicate with them was marvelous and mysterious at the same time. Roy didn’t so much train the animals as bond with them through a technique he called “affection conditioning,” raising tiger cubs from birth and sleeping with them until they were a year old. “When an animal gives you its trust,” Roy had said, “you feel like you have been given the most beautiful gift in the world.”

But on the night of October 3, that trust was broken. Forty-five minutes into the show, at about 8:15 p.m., Roy led out Mantacore, a seven-year-old white tiger born in Guadalajara, Mexico. The 380-pound cat became distracted by someone in the 1,500- member crowd and broke his routine, straying toward the edge of the stage. With no barrier protecting the audience, Roy leapt to put himself between Mantacore and the front row, only a few feet away. The tiger kept coming. Roy gave him a command to lie down, and Mantacore refused, gripping the trainer’s right wrist with his paw.

Willi Schneider/Shutterstock

“He lost the chain [around the tiger’s neck] and grabbed for it, but couldn’t get it,” says Tony Cohen, a Miami tourist who was sitting ten yards from the stage. With his free hand holding a wireless microphone, Roy tried repeatedly tapping Mantacore on the head, the sound reverberating through the theater. “Release!” Roy commanded the tiger. “Release!”

Mantacore relaxed his grip, but Roy had been straining to pull away, and fell backward over the tiger’s leg. In an instant, Mantacore was on top of him, clamping his powerful jaws around Roy’s neck. Now Siegfried, standing nearby, ran across the stage yelling, “No, no, no!” But the tiger was resolute, and dragged his master 30 feet offstage “literally like a rag doll,” as another witness recalls.

A couple of gasps went up in the crowd, though many people thought the incident was part of the act. “It wasn’t like he grabbed him viciously,” says audience member Andrew Cushman. “He just grabbed him by the throat and walked offstage.”

Siegfried would later say that Roy had fallen ill from the effects of blood pressure pills; Mantacore, he insisted, realized something was wrong and was only trying to protect Roy. But animal behaviorists put little stock into that notion. They say it’s more likely that Mantacore was on his way to delivering a killing bite, much as a tiger in the wild would bring down an antelope.

“They’re predators, so who can really know what goes on in their minds?” says Kay Rosaire, who runs the Big Cat Encounter, a show near Sarasota, Florida. “Even though they’re raised in captivity and they love us, sometimes their natural instincts just take over.”

Some members of the show who witnessed the incident say the cat didn’t necessarily mean to kill, but was confused by the break in the routine and angry at being disciplined. They believe the stress of the situation caused Mantacore to turn on the man who had worked with him almost daily from the time he was six months old.

Whatever the cause, horrified stagehands backstage sprayed the tiger with a fire extinguisher to get him to free Roy. When that failed, they beat the animal about the head with the butt end of the extinguisher. Mantacore finally ran to his cage. The tiger, they later learned, had torn Roy’s jugular vein, barely missing the carotid artery.

“There was a lot of blood,” reports dancer Mike Davies. “A lot.” Roy, still conscious, muttered, “Don’t shoot the cat.” A crew member managed to temporarily stop the severe bleeding, while cast members formed a prayer circle. Meanwhile, a trauma team assembled at University Medical Center, and as Roy labored to breathe, an ambulance screamed through the neon night. Before the story hit the papers, producer Kenneth Feld had canceled the 13-year-old show, telling more than 200 cast members to look for other work. Siegfried & Roy, the most popular act in the history of Vegas, was apparently over.

Laura Rauch/AP/Shutterstock

The news spread quickly through the all-night community, and vigils sprang up at the hospital and at the Mirage. Along the Strip, few performers were more admired than these two, who met as young men working on a German cruise ship. When they brought their magic act to Vegas in 1967 they helped transform a town then ruled by crooners, off-color comics and topless dancers. In 1988 they signed a record-breaking, five-year, $57 million deal with casino developer Steve Wynn to stage a Broadway-meets-Barnum & Bailey extravaganza at the Mirage, then still under construction.

Soon they were Vegas royalty, living in an opulent compound they called the Jungle Palace, where a replica of the Sistine Chapel adorned the ceiling—as well as a separate 100-acre estate, Little Bavaria, outside of town. There, 63 tigers and 16 lions, none of them declawed, had the run of the properties, including Roy’s bedroom and the pool. Roy meditated with at least one tiger every day.

While enormously wealthy, Siegfried and Roy were also incredibly generous. In particular, they were benefactors of the local police canine corps and the USO. As they told interviewers over the years, they were awed that, in Vegas, two sons of abusive, alcoholic fathers—both soldiers in Hitler’s army—were able to achieve their dreams and so much more.

Siegfried, who was always somewhat wary of the big beasts, was the intense, quiet one, the consummate magician and technical wizard, the brain behind the disappearing acts. Roy had his own animal magnetism and could command the big cats with the flick of a finger. Siegfried and Roy, says their friend Robin Leach, “are so closely intertwined they’re like brothers. Without one, there isn’t the other. They have an extraordinary relationship—the real meaning of the word love—that most people would want, particularly married couples.” Or as Siegfried puts it, “It has always been about together.”

At the hospital the night of the attack, Siegfried was in shock, recalled his friends Robert and Melinda Macy, who wrote a souvenir book Gift for the Ages with the pair. On the way to the trauma center, paramedics had stanched Roy’s massive blood loss, and he was immediately taken into surgery. There, the medical team had to bring him back from the edge at least three times.

Shortly after 11:30 p.m., they wheeled him out of the unit and into another part of the hospital. But early the next morning, Roy suffered a “pretty big stroke,” in the words of one physician, and was returned to surgery at 9:30, where doctors performed a large decompressive craniectomy, temporarily removing about a quarter of his skull to relieve swelling on his brain. (The excised portion was placed in a pouch in his abdomen to keep the bone tissue alive.) He suffered some paralysis on his left side, and his windpipe was crushed. Placed on a ventilator, he was unable to swallow or speak.

Yet amazingly, he responded to Steve Wynn only days later, squeezing his hand once for “yes” and twice for “no,” and answering in the affirmative when asked if he could handle such an ordeal. He also indicated that he wanted to see his pug-nosed dog, Piaf, who was brought to the hospital for a visit. “It is all but miraculous that he is alive,” his neurosurgeon, Dr. Derek Duke, told the press.

Late in October, Roy Horn was strong enough to be airlifted to the UCLA Medical Center, where he continued to make progress. And all the while, Siegfried stayed by his side. The first time he put a pen in Roy’s palm, Fischbacher touchingly recounted that his friend wrote, “Siegfried, it is nice to hold your hand.”

According to the duo’s manager, Bernie Yuman, Roy was taken off the ventilator in mid-November. His cognitive skills were “intact, perfect,” Yuman said. The entertainer was writing prolific notes, giving orders in them, even asking for a Madonna CD.

In the months following, the duo’s camp was largely silent, as was the show’s producer, Kenneth Feld, owner of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Feld had troubles other than Roy’s injuries: Animal rights groups have loudly insisted that show tigers should be retired. And the U.S. Department of Agriculture did open an investigation into a possible violation of the Animal Welfare Act, since regulations call for sufficient distance between animals and the viewing public in live-animal shows. With the stakes so high, the Mirage refused to release a tape of the near-fatal performance.

While Siegfried and Roy’s spokesmen couldn’t promise that the live show would come back, if anyone can make a full recovery from such a horrendous blow, says Bob Macy, it is Roy.

And it may not be his last. Because of the loss of blood and oxygen to the brain, physicians said that Roy could have experienced some irreversible paralysis and brain damage, and may always need assistance even with basic activities, including walking. Often in cases like Roy Horn’s, a patient also exhibits residual effects of brain injury such as speech difficulties, memory problems, emotional instability, and impaired critical thinking skills.

“My impression is that he had a significant injury that may prevent any type of return to their act,” says Catherine Cooper, MD, an anesthesiologist in Richmond, Virginia, who has studied stroke and brain injury cases. “His motor function is unlikely to improve substantially, and although his mental function is already better than initially feared, his neurological recovery will be a slow process, measured in very small accomplishments.”

But they are evident. By late January, his tracheal tube was out, allowing him to talk and ask for two of his favorite foods, pistachio ice cream and Wiener schnitzel. His mobility, too, had improved. Siegfried reported that Roy was standing up, and Yuman hinted he could be walking soon.

Still, those bright signs might not be enough to ensure Roy’s return to the stage, and he may finally be ready to take that retirement he spoke of at his birthday party. If so, he will likely find some way to contribute, his friends say, if only at the “Secret Garden,” the lush animal habitat behind the Mirage where Mantacore now paces and fixes his visitors with icy blue eyes.

Siegfried says he would never take another partner. There’s no need, he says; Roy will be back. “Roy is bigger than life. He always explained to me, ‘Life is full of miracles.’ ”

* * *

Controversy and rumors still surround exactly why the attack happened. In a recent ABC 20/20 documentary, Siegfried & Roy: Behind the Magic, Roy says that he became dizzy and suffered a stroke on stage that resulted in him falling to the floor. He claims that Mantacore saw he was in distress and dragged him to safety offstage. But, one of the trainers, Chris Lawrence, says that Mantacore wasn’t acting as a hero at all, rather that he became confused and deliberately attacked Roy on stage that night. Lawrence said that Mantacore missed his mark and Roy directed him in a way that he wasn’t used to, which caused the tiger to lung towards Roy, Roy fall on the ground, and Mantacore attack him. He thinks that the pair never admitted the truth about the attack because they didn’t want to ruin the image they had built around their relationships with the tigers.

The duo did get back on the stage one more time in 2009 for a final show. After the show abruptly stopped in 2003 from the attack they wanted to end their performance days on a high. Even though the pair wasn’t able to move around and perform illusions quite like they used to, they still put on a great show and even brought Mantacore out for one final trick on stage.

Click here to view full article