Learn about brain health and nootropics to boost brain function

Text Generation with Python and TensorFlow/Keras

Introduction

Are you interested in using a neural network to generate text? TensorFlow and Keras can be used for some amazing applications of natural language processing techniques, including the generation of text.

In this tutorial, we'll cover the theory behind text generation using a Recurrent Neural Networks, specifically a Long Short-Term Memory Network, implement this network in Python, and use it to generate some text.

Defining Terms

To begin with, let's start by defining our terms. It may prove difficult to understand why certain lines of code are being executed unless you have a decent understanding of the concepts that are being brought together.

TensorFlow

TensorFlow is one of the most commonly used machine learning libraries in Python, specializing in the creation of deep neural networks. Deep neural networks excel at tasks like image recognition and recognizing patterns in speech. TensorFlow was designed by Google Brain, and its power lies in its ability to join together many different processing nodes.

Keras

Meanwhile, Keras is an application programming interface or API. Keras makes use of TensorFlow's functions and abilities, but it streamlines the implementation of TensorFlow functions, making building a neural network much simpler and easier. Keras' foundational principles are modularity and user-friendliness, meaning that while Keras is quite powerful, it is easy to use and scale.

Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is exactly what it sounds like, the techniques used to enable computers to understand natural human language, rather than having to interface with people through programming languages. Natural language processing is necessary for tasks like the classification of word documents or the creation of a chatbot.

Corpus

A corpus is a large collection of text, and in the machine learning sense a corpus can be thought of as your model's input data. The corpus contains the text you want the model to learn about.

It is common to divide a large corpus into training and testing sets, using most of the corpus to train the model on and some unseen part of the corpus to test the model on, although the testing set can be an entirely different set of data. The corpus typically requires preprocessing to become fit for usage in a machine learning system.

Encoding

Encoding is sometimes referred to as word representation and it refers to the process of converting text data into a form that a machine learning model can understand. Neural networks cannot work with raw text data, the characters/words must be transformed into a series of numbers the network can interpret.

The actual process of converting words into number vectors is referred to as "tokenization", because you obtain tokens that represent the actual words. There are multiple ways to encode words as number values. The primary methods of encoding are one-hot encoding and creating densely embedded vectors.

We'll go into the difference between these methods in the theory section below.

Recurrent Neural Network

A basic neural network links together a series of neurons or nodes, each of which take some input data and transform that data with some chosen mathematical function. In a basic neural network, the data has to be a fixed size, and at any given layer in the neural network the data being passed in is simply the outputs of the previous layer in the network, which are then transformed by the weights for that layer.

In contrast, a Recurrent Neural Network differs from a "vanilla" neural network thanks to its ability to remember prior inputs from previous layers in the neural network.

To put that another way, the outputs of layers in a Recurrent Neural Network aren't influenced only by the weights and the output of the previous layer like in a regular neural network, but they are also influenced by the "context" so far, which is derived from prior inputs and outputs.

Recurrent Neural Networks are useful for text processing because of their ability to remember the different parts of a series of inputs, which means that they can take the previous parts of a sentence into account to interpret context.

Long Short-Term Memory

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTMs) networks are a specific type of Recurrent Neural Networks. LSTMs have advantages over other recurrent neural networks. While recurrent neural networks can usually remember previous words in a sentence, their ability to preserve the context of earlier inputs degrades over time.

The longer the input series is, the more the network "forgets". Irrelevant data is accumulated over time and it blocks out the relevant data needed for the network to make accurate predictions about the pattern of the text. This is referred to as the vanishing gradient problem.

You don't need to understand the algorithms that deal with the vanishing gradient problem (although you can read more about it here), but know that an LSTM can deal with this problem by selectively "forgetting" information deemed nonessential to the task at hand. By suppressing nonessential information, the LSTM is able to focus on only the information that genuinely matters, taking care of the vanishing gradient problem. This makes LSTMs more robust when handling long strings of text.

Text Generation Theory/Approach

Encoding Revisited

As previously mentioned, there are two main ways of encoding text data. One method is referred to as one-hot encoding, while the other method is called word embedding.

The process of one-hot encoding refers to a method of representing text as a series of ones and zeroes. A vector containing all possible words you are interested in, often all the words in the corpus, is created and a single word is represented by a "one" value in its respective position. Meanwhile all other positions (all the other possible words) are given a zero value. A vector like this is created for every word in the feature set, and when the vectors are joined together the result is a matrix containing binary representations of all the feature words.

Here's another way to think about this: any given word is represented by a vector of ones and zeroes, with a one value at a unique position. The vector is essentially concerned with answering the question: "Is this the target word?" If the word in the list of feature words is the target a positive value (one) is entered there, and in all other cases the word isn't the target, so a zero is entered. Therefore, you have a vector that represents just the target word. This is done for every word in the list of features.

One-hot encodings are useful when you need to need to create a bag of words, or a representation of words that takes their frequency of occurrence into account. Bag of words models are useful because although they are simple models, they still maintain a lot of important information and are versatile enough to be used for many different NLP related tasks.

One drawback to using one-hot encodings is that they cannot represent the meaning of a word, nor can they easily detect similarities between words. If meaning and similarity are concerns, word embeddings are often used instead.

Word embedding refers to representing words or phrases as a vector of real numbers, much like one-hot encoding does. However, a word embedding can use more numbers than simply ones and zeros, and therefore it can form more complex representations. For instance, the vector that represents a word can now be comprised of decimal values like 0.5. These representations can store important information about words, like relationship to other words, their morphology, their context, etc.

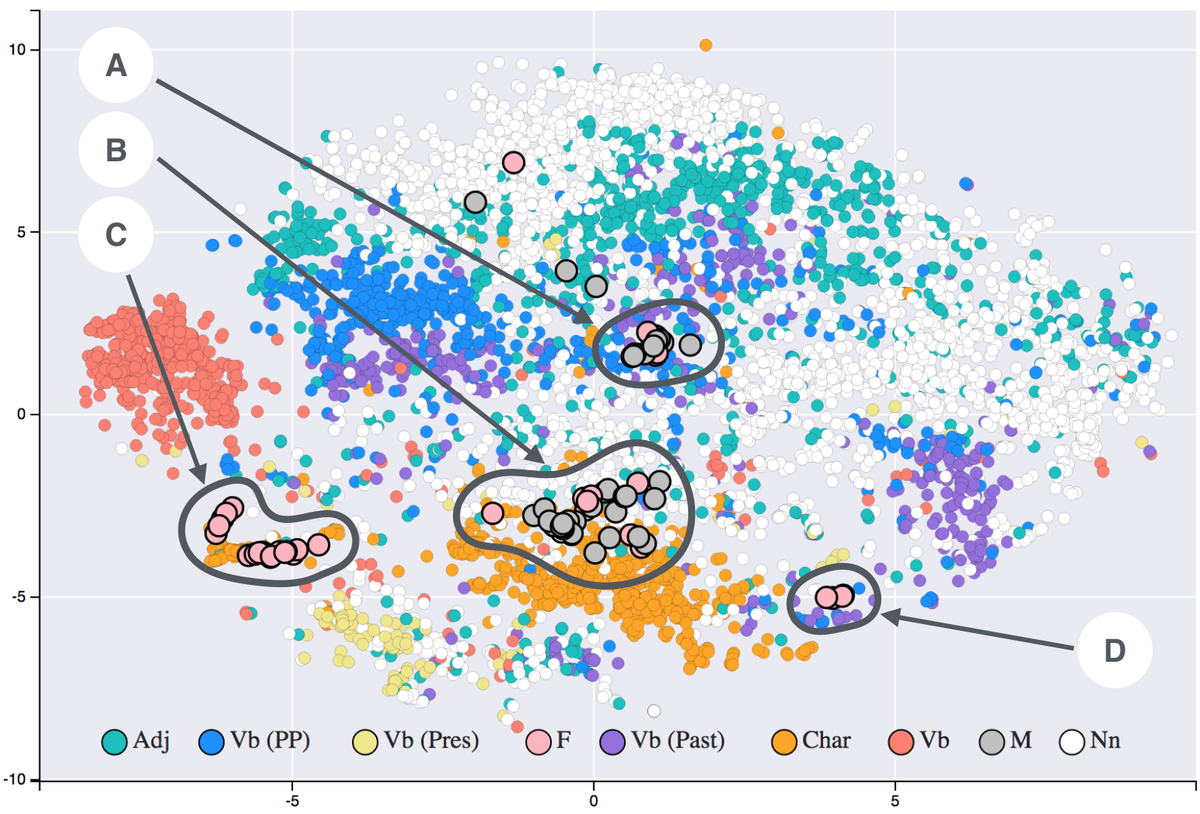

Word embeddings have fewer dimensions than one-hot encoded vectors do, which forces the model to represent similar words with similar vectors. Each word vector in a word embedding is a representation in a different dimension of the matrix, and the distance between the vectors can be used to represent their relationship. Word embeddings can generalize because semantically similar words have similar vectors. The word vectors occupy a similar region of the matrix, which helps capture context and semantics.

In general, one-hot vectors are high-dimensional but sparse and simple, while word embeddings are low dimensional but dense and complex.

Word-Level Generation vs Character-Level Generation

There are two ways to tackle a natural language processing task like text generation. You can analyze the data and make predictions about it at the level of the words in the corpus or at the level of the individual characters. Both character-level generation and word-level generation have their advantages and disadvantages.

In general, word-level language models tend to display higher accuracy than character-level language models. This is because they can form shorter representations of sentences and preserve the context between words easier than character-level language models. However, large corpuses are needed to sufficiently train word-level language models, and one-hot encoding isn't very feasible for word level models.

In contrast, character-level language models are often quicker to train, requiring less memory and having faster inference than word-based models. This is because the "vocabulary" (the number of training features) for the model is likely to be much smaller overall, limited to some hundreds of characters rather than hundreds of thousands of words.

Character-based models also perform well when translating words between languages because they capture the characters which make up words, rather than trying to capture the semantic qualities of words. We'll be using a character-level model here, in part because of its simplicity and fast inference.

Using an RNN/LSTM

When it comes to implementing an LSTM in Keras, the process is similar to implementing other neural networks created with the sequential model. You start by declaring the type of model structure you are going to use, and then add layers to the model one at a time. LSTM layers are readily accessible to us in Keras, we just have to import the layers and then add them with model.add.

In between the primary layers of the LSTM, we will use layers of dropout, which helps prevent the issue of overfitting. Finally, the last layer in the network will be a densely connected layer that will use a sigmoid activation function and output probabilities.

Sequences and Features

It is important to understand how we will be handling our input data for our model. We will be dividing the input words into chunks and sending these chunks through the model one at a time.

The features for our model are simply the words we are interested in analyzing, as represented with the bag of words. The chunks that we divide the corpus into are going to be sequences of words, and you can think of every sequence as an individual training instance/example in a traditional machine learning task.

Implementing an LSTM for Text Generation

Now we'll be implementing a LSTM and doing text generation with it. First, we'll need to get some text data and preprocess the data. After that, we'll create the LSTM model and train it on the data. Finally, we'll evaluate the network.

For the text generation, we want our model to learn probabilities about what character will come next, when given a starting (random) character. We will then chain these probabilities together to create an output of many characters. We first need to convert our input text to numbers and then train the model on sequences of these numbers.

Let's start out by importing all the libraries we're going to use. We need numpy to transform our input data into arrays our network can use, and we'll obviously be using several functions from Keras.

We'll also need to use some functions from the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) to preprocess our text and get it ready to train on. Finally, we'll need the sys library to handle the printing of our text:

import numpy

import sys

from nltk.tokenize import RegexpTokenizer

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.layers import Dense, Dropout, LSTM

from keras.utils import np_utils

from keras.callbacks import ModelCheckpoint

To start off with, we need to have data to train our model on. You can use any text file you'd like for this, but we'll be using part of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, which is available for download at Project Gutenburg, which hosts public domain texts.

We'll be training the network on the text from the first 9 chapters:

file = open("frankenstein-2.txt").read()

Let's start by loading in our text data and doing some preprocessing of the data. We're going to need to apply some transformations to the text so everything is standardized and our model can work with it.

We're going to lowercase everything so and not worry about capitalization in this example. We're also going to use NLTK to make tokens out of the words in the input file. Let's create an instance of the tokenizer and use it on our input file.

Finally, we're going to filter our list of tokens and only keep the tokens that aren't in a list of Stop Words, or common words that provide little information about the sentence in question. We'll do this by using lambda to make a quick throwaway function and only assign the words to our variable if they aren't in a list of Stop Words provided by NLTK.

Let's create a function to handle all that:

def tokenize_words(input):

# lowercase everything to standardize it

input = input.lower()

# instantiate the tokenizer

tokenizer = RegexpTokenizer(r'\w+')

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(input)

# if the created token isn't in the stop words, make it part of "filtered"

filtered = filter(lambda token: token not in stopwords.words('english'), tokens)

return " ".join(filtered)

Now we call the function on our file:

# preprocess the input data, make tokens

processed_inputs = tokenize_words(file)

A neural network works with numbers, not text characters. So well need to convert the characters in our input to numbers. We'll sort the list of the set of all characters that appear in our input text, then use the enumerate function to get numbers which represent the characters. We then create a dictionary that stores the keys and values, or the characters and the numbers that represent them:

chars = sorted(list(set(processed_inputs)))

char_to_num = dict((c, i) for i, c in enumerate(chars))

We need the total length of our inputs and total length of our set of characters for later data prep, so we'll store these in a variable. Just so we get an idea of if our process of converting words to characters has worked thus far, let's print the length of our variables:

input_len = len(processed_inputs)

vocab_len = len(chars)

print ("Total number of characters:", input_len)

print ("Total vocab:", vocab_len)

Here's the output:

Total number of characters: 100581

Total vocab: 42

Now that we've transformed the data into the form it needs to be in, we can begin making a dataset out of it, which we'll feed into our network. We need to define how long we want an individual sequence (one complete mapping of inputs characters as integers) to be. We'll set a length of 100 for now, and declare empty lists to store our input and output data:

seq_length = 100

x_data = []

y_data = []

Now we need to go through the entire list of inputs and convert the characters to numbers. We'll do this with a for loop. This will create a bunch of sequences where each sequence starts with the next character in the input data, beginning with the first character:

# loop through inputs, start at the beginning and go until we hit

# the final character we can create a sequence out of

for i in range(0, input_len - seq_length, 1):

# Define input and output sequences

# Input is the current character plus desired sequence length

in_seq = processed_inputs[i:i + seq_length]

# Out sequence is the initial character plus total sequence length

out_seq = processed_inputs[i + seq_length]

# We now convert list of characters to integers based on

# previously and add the values to our lists

x_data.append([char_to_num[char] for char in in_seq])

y_data.append(char_to_num[out_seq])

Now we have our input sequences of characters and our output, which is the character that should come after the sequence ends. We now have our training data features and labels, stored as x_data and y_data. Let's save our total number of sequences and check to see how many total input sequences we have:

n_patterns = len(x_data)

print ("Total Patterns:", n_patterns)

Here's the output:

Total Patterns: 100481

Now we'll go ahead and convert our input sequences into a processed numpy array that our network can use. We'll also need to convert the numpy array values into floats so that the sigmoid activation function our network uses can interpret them and output probabilities from 0 to 1:

X = numpy.reshape(x_data, (n_patterns, seq_length, 1))

X = X/float(vocab_len)

We'll now one-hot encode our label data:

y = np_utils.to_categorical(y_data)

Since our features and labels are now ready for the network to use, let's go ahead and create our LSTM model. We specify the kind of model we want to make (a sequential one), and then add our first layer.

We'll do dropout to prevent overfitting, followed by another layer or two. Then we'll add the final layer, a densely connected layer that will output a probability about what the next character in the sequence will be:

model = Sequential()

model.add(LSTM(256, input_shape=(X.shape[1], X.shape[2]), return_sequences=True))

model.add(Dropout(0.2))

model.add(LSTM(256, return_sequences=True))

model.add(Dropout(0.2))

model.add(LSTM(128))

model.add(Dropout(0.2))

model.add(Dense(y.shape[1], activation='softmax'))

We compile the model now, and it is ready for training:

model.compile(loss='categorical_crossentropy', optimizer='adam')

It takes the model quite a while to train, and for this reason we'll save the weights and reload them when the training is finished. We'll set a checkpoint to save the weights to, and then make them the callbacks for our future model.

filepath = "model_weights_saved.hdf5"

checkpoint = ModelCheckpoint(filepath, monitor='loss', verbose=1, save_best_only=True, mode='min')

desired_callbacks = [checkpoint]

Now we'll fit the model and let it train.

model.fit(X, y, epochs=4, batch_size=256, callbacks=desired_callbacks)

After it has finished training, we'll specify the file name and load in the weights. Then recompile our model with the saved weights:

filename = "model_weights_saved.hdf5"

model.load_weights(filename)

model.compile(loss='categorical_crossentropy', optimizer='adam')

Since we converted the characters to numbers earlier, we need to define a dictionary variable that will convert the output of the model back into numbers:

num_to_char = dict((i, c) for i, c in enumerate(chars))

To generate characters, we need to provide our trained model with a random seed character that it can generate a sequence of characters from:

start = numpy.random.randint(0, len(x_data) - 1)

pattern = x_data[start]

print("Random Seed:")

print("\"", ''.join([num_to_char[value] for value in pattern]), "\"")

Here's an example of a random seed:

" ed destruction pause peace grave succeeded sad torments thus spoke prophetic soul torn remorse horro "

Now to finally generate text, we're going to iterate through our chosen number of characters and convert our input (the random seed) into float values.

We'll ask the model to predict what comes next based off of the random seed, convert the output numbers to characters and then append it to the pattern, which is our list of generated characters plus the initial seed:

for i in range(1000):

x = numpy.reshape(pattern, (1, len(pattern), 1))

x = x / float(vocab_len)

prediction = model.predict(x, verbose=0)

index = numpy.argmax(prediction)

result = num_to_char[index]

seq_in = [num_to_char[value] for value in pattern]

sys.stdout.write(result)

pattern.append(index)

pattern = pattern[1:len(pattern)]

Let's see what it generated.

"er ed thu so sa fare ver ser ser er serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer serer...."

Does this seem somewhat disappointing? Yes, the text that was generated doesn't make any sense, and it seems to start simply repeating patterns after a little bit. However, the longer you train the network the better the text that is generated will be.

For instance, when the number of training epochs was increased to 20, the output looked more like this:

"ligther my paling the same been the this manner to the forter the shempented and the had an ardand the verasion the the dears conterration of the astore"

The model is now generating actual words, even if most of it still doesn't make sense. Still, for only around 100 lines of code, it isn't bad.

Now you can play around with the model yourself and try adjusting the parameters to get better results.

Conclusion

You'll want to increase the number of training epochs to improve the network's performance. However, you may also want to use either a deeper neural network (add more layers to the network) or a wider network (increase the number of neurons/memory units) in the layers.

You could also try adjusting the batch size, one hot-encoding the inputs, padding the input sequences, or combining any number of these ideas.

If you want to learn more about how LSTMs work, you can read up on the subject here. Learning how the parameters of the model influence the model's performance will help you choose which parameters or hyperparameters to adjust. You may also want to read up on text processing techniques and tools like those provided by NLTK.

If you'd like to read more about Natural Language Processing in Python, we've got a 12-part series that goes in-depth: Python for NLP.

You can also look at other implementations of LSTM text generation for ideas, such as Andrej Karpathy's blog post, which is one of the most famous uses of an LSTM to generate text.

Click here to view full article