Learn about brain health and nootropics to boost brain function

The Role of CRH in Negative Health Effects of Stress

Stress is harmful in numerous ways. This post focuses on one of the most important mediators of the negative effects of stress, but it’s not the only culprit.

If you have one or more of the following, you might have a stress-related issue (the more you have the more likely): “leaky gut”, “leaky brain”, mast cell/histamine issues, skin problems, sleep issues, SIBO, gut inflammation and general inflammation, IBS-Constipation, gut pain, diarrhea, problems gaining weight, anxiety/fear, depression, emotional instability, cognitive dysfunction, arthritis, Hashimoto’s, uveitis, IBD, disrupted circadian rhythm, oxidative stress, low testosterone and high estrogen, low libido and problems with fertility

If you’re reading this blog, you likely ticked off at least 5 of those. CRH is a common thread in all of these. Put your science hat and get ready for a technical read 🙂

Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH) is the first hormone of the HPA axis, and it’s released by the hypothalamus. CRH->ACTH->Cortisol.

Some people believe that CRH plays the largest role in gut permeability, which may ultimately be a significant cause of stress-induced food sensitivities.

CRH production takes place in the cerebral cortex, limbic system, cerebellum, locus coeruleus of the brain stem, and dorsal root neurons of the spinal cord.

It is also present in the adrenal medulla, T-lymphocytes of the immune system and the gastrointestinal tract [1].

The stress-response is classically divided into three categories: behavioral, autonomic, and hormonal responses.

CRH is believed to be involved in all three stress-responses, involving different brain regions [2].

Behavioral responses include muscle readiness, fear, anxiety, heightened vigilance, clarity of thought, decreased appetite, and decreased libido.

The behavioral response is initiated in part by the amygdala, which mediates fear-associated behavior.

The amygdalar CRH system is more sensitive to the psychological stressor than the hypothalamic CRH system given that psychological. The amygdalar CRH system causes wakefulness and arousal.

Autonomic responses are controlled by the hypothalamus and are responsible for the automated effects of sympathetic activation/fight-or-flight activation. These include increased heart rate, breathing rate, blood flow to the brain and muscles, activation of innate immunity, decreased blood flow to the skin, gut, and penis, activation of innate immunity, vasodilation and pupil dilation [3]. Other Autonomic functions include certain reflex actions such as coughing, sneezing, swallowing and vomiting.

CRH neurons connect to the brainstem, which is responsible for autonomic responses.

The hypothalamus is just above the brainstem and acts as an integrator for autonomic functions (receiving input from the limbic system to do so) [4].

The hormonal response provides fuel for such activities.

Some people with an overactive nervous system tend to have issues tolerating stressful situations. They are more likely to have anxiety, depression, emotional instability, and poor memory function. These symptoms may be caused – to one degree or another – by CRH.

CRH may cause fear and anxiety [5, 3] (via CRHR1[3]) and major depression [6]. CRH promotes anxiety in part by reducing cannabinoids in our amygdala.

This happens when CRH (CRHR1) increases FAAH in the amygdala, which causes a reduction in the endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA) [7].

Endocannabinoids balance the stress and anxiety responses. By disturbing their balance, CRH may cause enhanced emotionality i.e. emotional instability [7, 8].

In animal studies, CRH caused structural changes in hippocampal neurons, including reduced dendritic branching. This likely worsens memory [9].

CRH also accelerated cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease [10].

Acute stress can activate brain mast cells, which is dependent on CRH. This caused an increased blood-brain barrier permeability in rodents, particularly in brain areas containing mast cells (via CRHR-1) [11].

CRH receptors are decreased by chronic stress. This reduced feeding behavior and gastrointestinal motility in rats [12].

CRH and CCK: A Bad Synergy

One interesting study in mice found that long-term activation of the stress response (through CRH) worsened the anxiety effects of CCK (released after meals, especially those with lectins) and might lead to ‘hypersensitive emotional circuitry.’ This might be the case even if CRH isn’t elevated at the time of CCK secretion [13].

Additionally, mild stress caused long-lasting changes in CCK neurons in the prefrontal cortex of rats, which causes glutamate excitation [14].

Other animal studies show that CCK increases CRH and stress response. CCK may also cause anxiety independently of CRH, but both hormones potentiate each other [15, 13].

The master circadian timekeeper is in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus, which controls the HPA axis.

Preliminary evidence in hamsters suggests that CRH (via CRHR1) is very important to set the circadian rhythm (phase advance) in response to light [16].

Based on this study, people with too much CRH at night (from chronic stress or cortisol resistance) or too little in the morning may have problems with setting their circadian rhythm. Blocking CRH may counter the circadian disruption associated with depression and other stress-related disorders.

However, having normal CRH levels may be also important for the circadian rhythm, as CRH-deficient mice have a very low or absent rhythm in cortisol secretion [17].

CRH seems to decrease slow-wave sleep and increase REM, potentially helping people with sleep disturbances [18].

CRH increases glutamate excitotoxicity, which causes the breakdown of the mitochondria. This disturbs the energy balance of the cell, ultimately resulting in more oxidative stress.

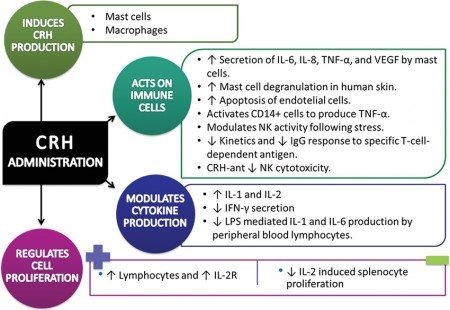

People with an overactive nervous system may suffer from inflammatory issues or immunodeficiency. Some may have lower blood pressure and issues with mast cells.

In skin cells, CRH increased Th1 dominance, Nf-kB, IL-1b (by 8.5X), IL-6 (7.3X), TNF (13X), MHC-II (HLA-DR) and ICAM-1 expression. Maximal inflammation was reached in an hour [22].

CRH also increased TLR-4 (a significant source of inflammation). Some people believe that this protein triggers food sensitivities (such as lectin sensitivity) when produced in the intestines [23].

CRH causes mast cell activation, nitric oxide-dependent vasodilatation (which lowers blood pressure), and the release of the WBC cytokine [24].

Mast cell activation by CRH could explain why stress may induce allergic symptoms [25].

CRH has been suggested to play an inflammatory role. It’s found in the joints of rheumatoid arthritis and uveitis patients, as well as in inflammatory immune cells [26].

In Hashimoto’s and ulcerative colitis, inflamed tissues have been found to contain large amounts of CRH [25].

Similarly, increased blood levels of CRH (and decreased skin CRHR-1) have been found in people with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis [27].

Some studies suggest that CRH inhibits NK cell activity [28], which may make you less capable of fighting viral infections. This effect may be prevented by Benzos [29] and beta-adrenergic antagonists [30]. Other studies show that CRH increases natural killer cell activity in mice (via an opioid pathway) [31].

Some people with an overactive nervous system tend to have gut problems such as altered intestinal flow and lower stomach acid (HCl) levels, which may cause bloating, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and intestinal inflammation.

CRH is a direct cause of IBS by increasing the flow or motor speed in the colon and decreasing it in the small intestine [32].

CRH may cause the gut to be ‘hypersensitive’ to pain. In clinical studies, giving a drug that blocks CRH relieved the pain [33].

CRH (via CRHR2) slowed small intestinal transit and quickened large intestinal transit in a small study on 20 people. This may cause IBS, most likely with constipation. However, genetic factors may trigger IBS with diarrhea [32].

CRH induced intestinal barrier injury (”leaky gut”) in pigs via the release of mast cell proteases and TNF-α [34].

The stimulatory effect on the colon may be mediated by the vagus nerve, 5-ht3 receptors, nicotinic receptors, muscarinic receptors, and CRF receptors of the brain stem (which GLP-1 activates [35, 36].

CRH inhibited stomach acid (HCl) secretion and stomach emptying in mice. CRH (CRHR1) caused intestinal inflammation and increased VEGF, ultimately triggering IBD [37].

CRH can also cause nausea by activating the 5-HT3 receptors (via serotonin), as seen in rat studies [39, 40].

It is possible that one of the CRH-related peptides (urocortin I or III) mediates some of the effects via the CRH receptors.

Clostridium difficile is an infectious bacteria that releases a toxin called “toxin A.” In mice, this toxin combined with high CRH levels causes increased substance P, intestinal (ileal) fluid secretion, cell damage, and neutrophils and myeloperoxidase to the gut [41].

CRH is believed to be an important cause of acne, psoriasis, eczema, alopecia areata, skin tumors and hives (urticaria) [42].

CRH may increase sebum (oily secretion) production. One mechanism is by CRH increasing testosterone in the skin [43].

CRH causes less VEGF in the skin. VEGF promotes hair growth and can, therefore, result in reduced hair growth or baldness.

CRH causes the release of IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 from skin cells and mast cells. All these may have the effect of reducing the skin immune system.

CRH activates mast cells in the skin, which may make you feel more flush. Mast cell activation plays a central role in skin issues such as eczema, itching, and hives.

CRH was increased in the skin of people with spot baldness (alopecia areata). However, they had insufficient cortisol. The effect of CRH on mast cells may contribute to less hair growth [44].

CRH and the resulting mast cell activation play an important role in contact dermatitis, which is a rash developed from a foreign substance. CRH increases the immune response to foreign substances and also increases inflammation (Nf-kB) in hair cells [42].

CRH enhanced tumor cell growth and angiogenesis and can cause or contribute to melanoma [45].

In human and animal studies, CRH (CRHR2) was an appetite suppressant that reduced body weight [46, 47, 48].

CRH is one of the factors causing lower appetite in anorexics. Both depression and anorexia are characterized by an elevated HPA axis, which in the case of anorexia seems to be driven by CRH [49, 50].

CRH dose-dependently reduced Ensure food intake in rats, being the effects potentiated by insulin. In response to high cortisol levels, blood sugar raises. This, in turn, causes insulin to be secreted [47].

CRH may cause the production of NPY both directly and indirectly by raising cortisol. Although NPY stimulates appetite, CRH is overall an appetite suppressant [51, 52].

Some people with an overactive nervous system tend to have hormonal issues. Some of these effects are likely mediated by CRH through the following mechanisms:

- CRH increases ACTH and cortisol.

- CRH inhibited GHRH in male rats, but not in females. GHRH is needed to produce growth hormone and increases slow-wave sleep. More significantly, stress increases GnIH, which directly inhibits GnRH [55].

- CRH inhibits estrogen and progesterone production in female reproductive cells, presumably having a negative impact on fertility [61].

There is considerable evidence that stress has a major negative effect on reproduction [62].

Intense or prolonged stress has been shown to inhibit gonadotropin (LH, FSH, hCG) secretion.

CRH has been implicated as a major inhibitor of reproductive function and libido in both sexes.

Experimental evidence suggests that the CRH Receptor 2 may be involved in vasodilation and blood pressure control (urocortin with over 20-fold higher affinity, compared with CRH) [62].

CRH activates orexin, causing wakefulness. This is one reason why we feel more awake at first when stressed [63, 64].

CRH increases ACTH, vasopressin and cortisol, which can be beneficial in certain situations [66].

Lack of the hormone CRH may result in feelings of extreme tiredness common to people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. Lack of CRH also seems to be central to seasonal affective disorder (SAD), the feelings of fatigue and depression that plague some people during winter months.

CRH enhanced superoxide production by macrophages in rabbits, possibly helping fight infections [20].

CRH may inhibit Nf-kB in some cases (via POMC), but may also increase it in other ways [68].

By stimulating insulin release, CRH may be antidiabetic [69].

CRH and Bad Signaling

Chronic stress increases CRH by decreasing negative feedback. This means CRH will not be inhibited by cortisol like it normally should [71].

Normally, after CRH is released, there’s also a spike in ACTH and cortisol, which feeds back to reduce CRH if you aren’t ‘resistant’ or ‘insensitive’ to the negative feedback from cortisol.

Genetic factors may prevent the cortisol (glucocorticoid) receptors from functioning right or reduce the ability of CRH to produce cortisol. In both cases, excess CRH is produced.[72].

In people with major depression, CRH doesn’t produce enough ACTH (and cortisol) [73].

Chronic mild stress (in mice) causes cortisol resistance by increasing nitric oxide in the hippocampus (via activating mineralocorticoid receptor), which decreases the cortisol/glucocorticoid receptors (via cGMP and peroxynitrite). This elevates CRH [74].

- See this post for a full list. This is only a partial list. Most of the time, anything that raises cortisol, raises CRH.

- Cortisol/Glucocorticoids inhibit CRH production in the hypothalamus. However, in the amygdala – a brain region involved in the behavioral stress response – cortisol increases CRH, leading to anxiety and fear [3].

- Acetylcholine, norepinephrine, histamine, and serotonin increase hypothalamic CRH release, while GABA inhibits it. Angiotensin, vasopressin, neuropeptide-Y, substance P, atrial natriuretic peptide, activin, melanin-concentrating hormone, and b-endorphin increase CRH [3].

- Hypoxia increases CRH in rats and doesn’t let CRH stimulate insulin (because of reduced ATP and cAMP and coincident loss of intracellular calcium oscillations) [75].

- Hypothyroidism increases CRH and AVP production in the hypothalamus of rats [78]. So hypothyroidism can stimulate your HPA axis. A lot of my clients have low T3.

To see if you have any genes affecting your CRH levels input your genetic data using our software, SelfDecode.

Want Better Ways to Improve Your Mood?

If you’re interested in natural and targeted ways of improving your mood, we recommend checking out SelfDecode’s Mood DNA Wellness Report. It gives genetic-based diet, lifestyle and supplement tips that can help improve your mood. The recommendations are personalized based on your genes.

SelfDecode is a sister company of SelfHacked. The proceeds from your purchase of this product are reinvested into our research and development, in order to serve you better. Thanks for your support!

Click here to view full article